【medical-news】The Lancet:孤独症(内容超长,请诸君耐心看完)

Volume 383, Issue 9920, 8–14 March 2014, Pages 896–910

Autism

Dr Meng-Chuan Lai, PhDa, b, Corresponding author contact information, E-mail the corresponding author,

Michael V Lombardo, PhDa, c,

Prof Simon Baron-Cohen, PhDa,

Summary

Autism is a set of heterogeneous neurodevelopmental conditions, characterised by early-onset difficulties in social communication and unusually restricted, repetitive behaviour and interests. The worldwide population prevalence is about 1%. Autism affects more male than female individuals, and comorbidity is common (>70% have concurrent conditions). Individuals with autism have atypical cognitive profiles, such as impaired social cognition and social perception, executive dysfunction, and atypical perceptual and information processing. These profiles are underpinned by atypical neural development at the systems level. Genetics has a key role in the aetiology of autism, in conjunction with developmentally early environmental factors. Large-effect rare mutations and small-effect common variants contribute to risk. Assessment needs to be multidisciplinary and developmental, and early detection is essential for early intervention. Early comprehensive and targeted behavioural interventions can improve social communication and reduce anxiety and aggression. Drugs can reduce comorbid symptoms, but do not directly improve social communication. Creation of a supportive environment that accepts and respects that the individual is different is crucial.

[img=554,2]file:///C:/Users/DEREKS~1/AppData/Local/Temp/ksohtml/wps_clip_image-1271.png[/img]

Definition

In 1943, child psychiatrist Leo Kanner described eight boys and three girls,1 including 5-year-old Donald who was “happiest when left alone, almost never cried to go with his mother, did not seem to notice his father's home-comings, and was indifferent to visiting relatives…wandered about smiling, making stereotyped movements with his fingers…spun with great pleasure anything he could seize upon to spin…. Words to him had a specifically literal, inflexible meaning…. When taken into a room, he completely disregarded the people and instantly went for objects”. In 1944, paediatrician Hans Asperger described four boys,2 including 6-year-old Fritz who “learnt to talk very early…quickly learnt to express himself in sentences and soon talked ‘like an adult’…never able to become integrated into a group of playing children…did not know the meaning of respect and was utterly indifferent to the authority of adults…lacked distance and talked without shyness even to strangers…it was impossible to teach him the polite form of address…. Another strange phenomenon…was the occurrence of certain stereotypic movements and habits”.

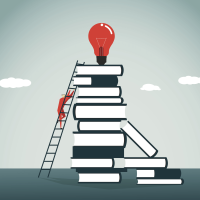

These seminal reports1 and 2 vividly portray what is now called autism or the autism spectrum. The spectrum is wide, encompassing classic Kanner's syndrome (originally entitled autistic disturbances of affective contact) and Asperger's syndrome (originally called autistic psychopathy in childhood). Understanding of autism has evolved substantially in the past 70 years, with an exponential growth in research since the mid-1990s (figure). Autism is now thought of as a set of neurodevelopmental conditions, some of which can be attributed to distinct aetiological factors, such as Mendelian single-gene mutations. However, most are probably the result of complex interactions between genetic and non-genetic risk factors. The many types are collectively defined by specific behaviours, centring on atypical development in social communication and unusually restricted or repetitive behaviour and interests.

Figure.

The growth of autism research

Almost three times as many reports about autism were published between 2000 and 2012 (n=16?741), as between 1940 and 1999 (n=6054). These calculations are based on a keyword search of PubMed with the term “‘autism’ OR ‘autism spectrum disorder’ OR ‘pervasive developmental disorder’ OR ‘Asperger syndrome’”.

Figure options

· Download full-size image

· Download high-quality image (115 K)

· Download as PowerPoint slide

The mid-20th century view of autism as a form of childhood psychosis is no longer held. The first operational definition appeared in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III), and was strongly influenced by Michael Rutter's conceptualisation of impaired social development and communicative development, insistence on sameness, and onset before 30 months of age.3 The subsequent revisions in the fourth edition (DSM-IV) and the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), in which autism was referred to as pervasive developmental disorder, emphasised the early onset of a triad of features: impairments in social interaction; impairments in communication; and restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped behaviour, interests, and activities.

The latest revision of DSM—DSM-5, published in May, 20134—adopted the umbrella term autism spectrum disorder without a definition of subtypes, and reorganised the triad into a dyad: difficulties in social communication and social interaction; and restricted and repetitive behaviour, interests, or activities (table 1). Atypical language development (historically linked to an autism diagnosis) was removed from the criteria, and is now classified as a co-occurring condition, even though large variation in language is characteristic of autism.5 The new criteria give improved descriptions and organisation of key features, emphasise the dimensional nature of autism, provide one diagnostic label with individualised specifiers, and allow for an assessment of the individual's need for support (helping provision of clinical services).6 How prevalence estimates will be affected by the new criteria and how autism spectrum disorder will relate to the newly created social (pragmatic) communication disorder (defined by substantial difficulties with social uses of both verbal and non-verbal communication, but otherwise not meeting criteria for autism spectrum disorder) remain to be assessed.

Table 1.

Behavioural characteristics of autism

| Core features in DSM-5 criteria* | |

| Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts | Deficits in social–emotional reciprocity Deficits in non-verbal communicative behaviours used for social interaction Deficits in developing, maintaining, and understanding relationships |

| Restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests, or activities | Stereotyped or repetitive motor movements, use of objects, or speech Insistence on sameness, inflexible adherence to routines, or ritualised patterns of verbal or non-verbal behaviour Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus Hyper-reactivity or hyporeactivity to sensory input or unusual interest in sensory aspects of the environment |

| Associated features not in DSM-5 criteria | |

| Atypical language development and abilities | Age <6 years: frequently deviant and delayed in comprehension; two-thirds have difficulty with expressive phonology and grammar Age ≥6 years: deviant pragmatics, semantics, and morphology, with relatively intact articulation and syntax (ie, early difficulties are resolved) |

| Motor abnormalities | Motor delay; hypotonia; catatonia; deficits in coordination, movement preparation and planning, praxis, gait, and balance |

| Excellent attention to detail | .. |

Epidemiology

Prevalence

The prevalence of autism has been steadily increasing since the first epidemiological study,7 which showed that 4·1 of every 10?000 individuals in the UK had autism. The increase is probably partly a result of changes in diagnostic concepts and criteria.8 However, the prevalence has continued to rise in the past two decades, particularly in individuals without intellectual disability, despite consistent use of DSM-IV criteria.9 An increase in risk factors cannot be ruled out. However, the rise is probably also due to improved awareness and recognition, changes in diagnosis, and younger age of diagnosis.10 and 11

Nowadays, the median worldwide prevalence of autism is 0·62–0·70%,10 and 11 although estimates of 1–2% have been made in the latest large-scale surveys.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 and 19 A similar prevalence has been reported for adults alone.20 About 45% of individuals with autism have intellectual disability,11 and 32% have regression (ie, loss of previously acquired skills; mean age of onset 1·78 years).21

Early studies showed that autism affects 4–5 times more males than females, although the difference decreased in individuals with intellectual disability.11 However, large-scale population-based studies12, 13, 16 and 19 have shown that 2–3 times more males are affected, probably irrespective of intellectual disability. Females with autism might have been under-recognised.22 Empirical data suggest high-functioning females are diagnosed later than males are,23 and 24 and indicate a diagnostic bias towards males.25 Females need more concurrent behavioural or cognitive problems than males do to be clinically diagnosed.26 This diagnostic bias might be a result of behavioural criteria for autism or gender stereotypes, and might reflect better compensation or so-called camouflage in females.6, 26, 27, 28 and 29

Nevertheless, a male predominance is a consistent epidemiological finding that has aetiological implications. It could imply female-specific protective effects, such that females would have to have a greater aetiological (genetic or environmental) load than would males to reach the diagnostic threshold. These protective effects would mean that relatives of female probands would have an increased risk of autism or more autistic characteristics than would relatives of male probands.30 Alternatively, male-specific risks could heighten susceptibility.22 and 31 The existence of sex-linked aetiological load and susceptibility emphasises the importance of stratification by sex, and of comparisons between males and females to disentangle the aetiological role of sex-linked factors at genetic, endocrine, epigenetic, and environmental levels.

Risk and protective factors

Epidemiological studies have identified various risk factors,32 but none has proven to be necessary or sufficient alone for autism to develop. Understanding of gene–environment interplay in autism is still at an early stage.33 Advanced paternal or maternal reproductive age, or both, is a consistent risk;34, 35 and 36 the underlying biology is unclear, but could be related to germline mutation, particularly when paternal in origin.37, 38, 39, 40 and 41 Alternatively, individuals who have children late in life might do so because they have the broader autism phenotype—ie, mild traits characteristic of autism—which is known to be associated with having a child with autism,42 although this idea needs further research. Additionally, prevalence of autism has been reported to be two times higher in cities where many jobs are in the information-technology sector than elsewhere; parents of children with autism might be more likely to be technically talented than are other parents.43

Gestational factors that could affect neurodevelopment, such as complications during pregnancy44 and 45 and exposure to chemicals,32, 46, 47, 48 and 49 have been suggested to increase risk of autism. A broad, non-specific class of conditions reflecting general compromises to perinatal and neonatal health is also associated with increased risk.50 Conversely, folic acid supplements before conception and during early pregnancy seem to be protective.51 There is no evidence that the MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine,52 thiomersal-containing vaccines,53 or repeated vaccination54 cause autism.

Co-occurring conditions

More than 70% of individuals with autism have concurrent medical, developmental, or psychiatric conditions (table 2)55, 56, 57, 58 and 59—a higher proportion than that for psychiatric outpatients60 and patients in tertiary hospitals.61 Childhood co-occurring conditions tend to persist into adolescence.62 Some co-occurring conditions, such as epilepsy and depression (table 2), can first develop in adolescence or adulthood. Generally, the more co-occurring conditions, the greater the individual's disability.58 The high frequency of comorbidity could be a result of shared pathophysiology, secondary effects of growing up with autism, shared symptom domains and associated mechanisms, or overlapping diagnostic criteria.

Table 2.

Common co-occurring conditions

| Developmental | ||

| Intellectual disability | ?45% | Prevalence estimate is affected by the diagnostic boundary and the definition of intelligence (eg, whether verbal ability is used as a criterion) In individuals, discrepant performance between subtests is common |

| Language disorders | Variable | In DSM-IV, language delay was a defining feature of autism (autistic disorder), but is no longer included in DSM-5 An autism-specific language profile (separate from language disorders) exists, but with substantial inter-individual variability |

| Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder | 28–44% | In DSM-IV, not diagnosed when occurring in individuals with autism, but no longer so in DSM-5 Clinical guidance available |

| Tic disorders | 14–38% | ?6·5% have Tourette's syndrome |

| Motor abnormality | ≤79% | See table 1 |

| General medical | ||

| Epilepsy | 8–30% | Increased frequency in individuals with intellectual disability or genetic syndromes Two peaks of onset: early childhood and adolescence Increases risk of poor outcome Clinical guidance available |

| Gastrointestinal problems | 9–70% | Common symptoms include chronic constipation, abdominal pain, chronic diarrhoea, and gastro-oesophageal reflux Associated disorders include gastritis, oesophagitis, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, inflammatory bowel disease, coeliac disease, Crohn's disease, and colitis Clinical guidance available |

| Immune dysregulation | ≤38% | Altered immune function, which interacts with neurodevelopment, could be a crucial biological pathway underpinning autism Associated with allergic and autoimmune disorders |

| Genetic syndromes | ?5% | Collectively called syndromic autism Examples include fragile × syndrome (21–50% of individuals affected have autism), Rett syndrome (most have autistic features but with profiles different from idiopathic autism), tuberous sclerosis complex (24–60%), Down's syndrome (5–39%), phenylketonuria (5–20%), CHARGE syndrome (coloboma of the eye; heart defects; atresia of the choanae; retardation of growth and development, or both; genital and urinary abnormalities, or both; and ear abnormalities and deafness; 15–50%), Angelman syndrome (50–81%), Timothy syndrome (60–70%), and Joubert syndrome (?40%) |

| Sleep disorders | 50–80% | Insomnia is the most common Clinical guidance available |

| Psychiatric | ||

| Anxiety | 42–56% | Common across all age groups Most common are social anxiety disorder (13–29% of individuals with autism; clinical guidance available) and generalised anxiety disorder (13–22%) High-functioning individuals are more susceptible (or symptoms are more detectable) |

| Depression | 12–70% | Common in adults, less common in children High-functioning adults who are less socially impaired are more susceptible (or symptoms are more detectable) |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 7–24% | Shares the repetitive behaviour domain with autism that could cut across nosological categories Important to distinguish between repetitive behaviours that do not involve intrusive, anxiety-causing thoughts or obsessions (part of autism) and those that do (and are part of obsessive-compulsive disorder) |

| Psychotic disorders | 12–17% | Mainly in adults Most commonly recurrent hallucinosis High frequency of autism-like features (even a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder or pervasive developmental disorder) preceding adult-onset (52%) and childhood-onset schizophrenia (30–50%) |

| Substance use disorders | ≤16% | Potentially because individual is using substances as self-medication to relieve anxiety |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 16–28% | Oppositional behaviours could be a manifestation of anxiety, resistance to change, stubborn belief in the correctness of own point of view, difficulty seeing another's point of view, poor awareness of the effect of own behaviour on others, or no interest in social compliance |

| Eating disorders | 4–5% | Could be a misdiagnosis of autism, particularly in females, because both involve rigid behaviour, inflexible cognition, self-focus, and focus on details |

| Personality disorders* | ||

| Paranoid personality disorder | 0–19% | Could be secondary to difficulty understanding others' intentions and negative interpersonal experiences |

| Schizoid personality disorder | 21–26% | Partly overlapping diagnostic criteria Similar to Wing's loners subgroup |

| Schizotypal personality disorder | 2–13% | Some overlapping criteria, especially those shared with schizoid personality disorder |

| Borderline personality disorder | 0–9% | Could have similarity in behaviours (eg, difficulties in interpersonal relationships, misattributing hostile intentions, problems with affect regulation), which requires careful differential diagnosis Could be a misdiagnosis of autism, particularly in females |

| Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder | 19–32% | Partly overlapping diagnostic criteria |

| Avoidant personality disorder | 13–25% | Could be secondary to repeated failure in social experiences |

| Behavioural | ||

| Aggressive behaviours | ≤68% | Often directed towards caregivers rather than non-caregivers Could be a result of empathy difficulties, anxiety, sensory overload, disruption of routines, and difficulties with communication |

| Self-injurious behaviours | ≤50% | Associated with impulsivity and hyperactivity, negative affect, and lower levels of ability and speech Could signal frustration in individuals with reduced communication, as well as anxiety, sensory overload, or disruption of routines Could also become a repetitive habit Could cause tissue damage and need for restraint |

| Pica | ?36% | More likely in individuals with intellectual disability Could be a result of a lack of social conformity to cultural categories of what is deemed edible, or sensory exploration, or both |

| Suicidal ideation or attempt | 11–14% | Risks increase with concurrent depression and behavioural problems, and after being teased or bullied |

*

Particularly in high-functioning adults.

Full-size table

Table options

· View in workspace

· Download as CSV

Prognosis and outcome

A meta-analysis63 showed that individuals with autism have a mortality risk that is 2·8 times higher (95% CI 1·8–4·2) than that of unaffected people of the same age and sex. This difference is mostly related to co-occurring medical conditions.64 Studies done before the widespread application of early intervention programmes65, 66 and 67 showed that 58–78% of adults with autism have poor or very poor outcomes in terms of independent living, educational attainment, employment, and peer relationships. Higher childhood intelligence, communicative phrase speech before age 6 years, and fewer childhood social impairments predict a better outcome.65, 66 and 67 Yet, even for individuals without intellectual disability, adult social outcome is often unsatisfactory in terms of quality of life and achievement of occupational potential,67 although it is associated with cognitive gain and improved adaptive functioning during development.68 Childhood follow-up studies have shown varying developmental trajectories in children with autism69 and 70 and in their siblings.71 The best possible outcome—ie, reversal of diagnosis, negligible autistic symptoms, and normal social communication—has also been reported.72

Transition to adulthood, which often involves loss of school support and child and adolescent mental health services, is a challenge. The end of secondary education is often accompanied by slowed improvement, probably due to reduced occupational stimulation73 and insufficient adult services.74 More than half of young people in the USA who have left secondary education in the past 2 years are not participating in any paid work or education.75 The mean proportion of adults with autism in employment (regular, supported, or sheltered) or full-time education is 46%.76 Furthermore, little is known about how ageing affects people with autism.76 and 77

Early signs and screening

Early identification allows early intervention. Previously, children with autism were often identified when older than 3–4 years, but toddlers are now frequently diagnosed because atypical development is recognised early. Early indicators are deficits or delays in the emergence of joint attention (ie, shared focus on an object) and pretend play, atypical implicit perspective taking, deficits in reciprocal affective behaviour, decreased response to own name, decreased imitation, delayed verbal and non-verbal communication, motor delay, unusually repetitive behaviours, atypical visuomotor exploration, inflexibility in disengaging visual attention, and extreme variation in temperament.78 and 79 These indicators contribute to screening and diagnostic instruments for toddlers.79 However, identification of high-functioning individuals is still often later than it should be,80 particularly for females.23 and 24

Variability in age, cognitive ability, and sex leads to differential presentation and the need for appropriate screening instruments (table 3). Care should be taken during selection of screening instruments (and the cutoff for further action), because the target sample and purpose of screening vary.81 Routine early screening at ages 18 and 24 months has been recommended.82 The advantages and disadvantages of action after a positive result should be carefully considered,83 as should the identification and management of individuals who have false-positive results.

Table 3.

Screening and diagnostic instruments

| Screening: young children | ||

| Checklist for autism in toddlers (CHAT) | 18 months | 14-item questionnaire: nine completed by parent or caregiver and five by primary health-care provider; takes 5–10 min |

| Early screening of autistic traits (ESAT) | 14 months | 14-item questionnaire: completed by health practitioners at well-baby visit after interviewing parent or caregiver; takes 5–10 min |

| Modified checklist for autism in toddlers (M-CHAT) | 16–30 months | 23-item questionnaire: completed by parent or caregiver; takes 5–10 min |

| Infant toddler checklist (ITC) | 6–24 months | 24-item questionnaire: completed by parent or caregiver; takes 5–10 min |

| Quantitative checklist for autism in toddlers (Q-CHAT) | 18–24 months | 25-item questionnaire: completed by parent or caregiver; takes 5–10 min; ten-item short version available |

| Screening tool for autism in children aged 2 years (STAT) | 24–36 months | 12 items and activities: assessed by clinician or researcher after interacting with the child; takes 20 min; intensive training necessary; level-two screening measure |

| Screening: older children and adolescents | ||

| Social communication questionnaire (SCQ) | >4 years (and mental age >2 years) | 40-item questionnaire: completed by parent or caregiver; takes 10–15 min |

| Social responsiveness scale, first or second edition (SRS, SRS-2) | >2·5 years | 65-item questionnaire: completed by parent, caregiver, teacher, relative, or friends (self-report form available for adult in SRS-2); takes 15–20 min |

| Childhood autism screening test (CAST) | 4–11 years | 37-item questionnaire: completed by parent or caregiver; takes 10–15 min |

| Autism spectrum screening questionnaire (ASSQ)* | 7–16 years | 27-item questionnaire: completed by parent, caregiver, or teacher; takes 10 min |

| Autism spectrum quotient (AQ), child and adolescent versions* | Child: 4–11 years; adolescent: 10–16 years | 50-item questionnaire: completed by parent or caregiver; takes 10–15 min; ten-item short versions available |

| Screening: adults | ||

| Autism spectrum quotient (AQ), adult version* | >16 years (with average or above-average intelligence) | 50-item questionnaire: self-report; takes 10–15 min; ten-item short version available |

| The Ritvo autism Asperger diagnostic scale-revised (RAADS-R) | >18 years (with average or above-average intelligence) | 80-item questionnaire: self-report; done with a clinician; takes 60 min |

| Diagnosis: structured interview | ||

| The autism diagnostic interview-revised (ADI-R) | Mental age >2 years | 93-item interview of parent or caregiver; takes 1·5–3 h; intensive training necessary |

| The diagnostic interview for social and communication disorders (DISCO) | All chronological and mental ages | 362-item interview of parent or caregiver; takes 2–4 h; intensive training necessary |

| The developmental, dimensional, and diagnostic interview (3Di) | >2 years | 266-item computer-assisted interview of parent or caregiver; takes 2 h; 53-item short form available, which takes 45 min; intensive training necessary |

| Diagnosis: observational measure | ||

| The autism diagnostic observation schedule, first or second edition (ADOS, ADOS-2) | >12 months | Clinical observation via interaction: select one from five available modules according to expressive language level and chronological age; takes 40–60 min; intensive training necessary |

| Childhood autism rating scale, first or second edition (CARS, CARS-2) | >2 years | 15-item rating scale: completed by clinician or researcher; takes 20–30 min; accompanied by a questionnaire done by parent or caregiver; moderate training necessary |

Clinical assessment

Diagnostic assessment should be multidisciplinary and use a developmental framework of an interview with the parent or caregiver, interaction with the individual, collection of information about behaviour in community settings (eg, school reports and job performance), cognitive assessments, and a medical examination.92 Co-occurring conditions should be carefully screened.

The interview of the parent or caregiver should cover the gestational, birth, developmental, and health history, and family medical and psychiatric history. It should have specific foci: the development of social, emotional, language and communication, cognitive, motor, and self-help skills; the sensory profile; and unusual behaviours and interests. Behavioural presentation across different contexts should be investigated. Ideally, a standardised, structured interview should be incorporated into the assessment process (table 3). Adaptive skills should be checked with standardised instruments (eg, Vineland adaptive behaviour scales). In children, parent–child interaction and parent coping strategies should be specifically investigated, because they are relevant for the planning of interventions.

Interviews with the individual should be interactive and engaging to enable assessment of social-communication characteristics in both structured and unstructured contexts. Again, information should ideally be gathered with standardised instruments (table 3). For adolescents and adults capable of reporting their inner state, self-report questionnaires are helpful (table 3), but their validity should be weighed against the individual's level of insight. How individuals cope in a peer environment should also be assessed.

School reports and job performance records are valuable data indicating an individual's strengths and difficulties in real-life settings. They also help with individualisation of educational and occupational planning. Cognitive assessments of intelligence and language are essential; standardised, age-appropriate, and development-appropriate instruments should be used to measure both verbal and non-verbal ability.92 Neuropsychological assessments are helpful for individualised diagnosis and service planning.

A medical examination is important in view of the high frequency of comorbidity. Physical and neurological examinations (eg, head circumference, minor physical anomalies and skin lesions, and motor function)93 and genetic analyses (eg, G-banded karyotype analysis, FMR1 testing, and particularly chromosomal microarray analysis) 94 and 95 should be done. Other laboratory tests—eg, electroencephalography when awake and asleep if seizures are suspected, neuroimaging when intracranial lesions are suspected, and metabolic profiling when neurometabolic disorders are suspected—can be done as necessary.

Cognition and neuroscience

In the mid-20th century, autism was thought to originate from the emotional coldness of the child's mother, even though this hypothesis had no empirical support. By contrast, concurrent neurobiological hypotheses96 and Kanner's proposal of an “innate inability to form the usual, biologically provided affective contact with people”1 have received scientific support. Cognition and neurobiology are related, and their development is characterised by a complex interplay between innate and environmental factors. Cognition provides a guide to simplify the various behavioural manifestations of autism, and can help investigation of underpinning neurobiology.97 Cognitive perspectives of autism can be grouped according to domains of concern (table 4), although they are by nature interlinked.

Table 4.

Cognitive domains in autism research

| Social cognition and social perception | Atypical social interaction and social communication | Gaze and eye contact; emotion perception; face processing; biological motion perception; social attention and orienting; social motivation; social reward processing; non-verbal communication; imitation; affective empathy and sympathy; joint attention; pretend play; theory of mind or mental perspective taking; self-referential cognition; alexithymia (difficulty understanding and describing own emotions); metacognitive awareness |

| Executive function | Repetitive and stereotyped behaviour; atypical social interaction and social communication | Cognitive flexibility; planning; inhibitory control; attention shifting; monitoring; generativity; working memory |

| Bottom-up and top-down (local vs global) information processing * | Idiosyncratic sensory-perceptual processing; excellent attention to detail; restricted interests and repetitive behaviour; atypical social interaction and social communication | Global vs local perceptual functioning (superior low-level sensory-perceptual processing); central coherence (global vs local preference); systemising (drive to construct rule-based systems, ability to understand rule-based systems, knowledge of factual systems) |

Although many (high-functioning) individuals with autism achieve some degree of explicit or controlled mentalising,101 the implicit, automatic, and intuitive components are still impaired, even in adulthood.102 Early-onset mentalising difficulties seem to be specific to autism, but late-onset deficits are reported in disorders such as schizophrenia.103 Mentalising is closely entwined with executive control and language,104 so that the dichotomous view of social versus non-social cognition is potentially misleading in autism.

Historically, the domain of mentalising has been largely centred on others, but self-referential cognition and its neural substrates are also atypical in autism.105 and 106 Therefore, deficits in the social domain are not only about difficulties in the processing of information about other people, but also about processing of self-referential information, the relationship that self has in a social context, and the potential for using self as a proxy to understand the social world.

A consistent network of brain regions—including the medial prefrontal cortex, superior temporal sulcus, temporoparietal junction, amygdala, and fusiform gyrus—are hypoactive in autism across tasks in which social perception and cognition are used.100, 107 and 108 Dysfunction in the so-called mirror system (ie, brain regions that are active both when an individual performs an action and observes another person performing the same action) has been inconsistently implicated in imitation or observation of action or emotion in autism.109 However, brain structures do not act separately. Although studies of autism showing atypical development of the so-called social brain are promising,100 equal attention should be paid to how these brain structures interact with the rest of the neural system.

Executive dysfunction could underlie both the unusually repetitive stereotyped behaviours and social-communication deficits in autism (table 4). However, the consistency of reports has been challenged,110 and impaired performance could be underpinned by difficulties with mentalising.111 Imaging studies have shown that frontal, parietal, and striatal circuitry are the main systems implicated in executive dysfunction in autism.107 and 108 Executive dysfunction is not specific to autism; it is commonly reported in other neuropsychiatric conditions (although with different patterns). One view is that strong executive function early in life could protect at-risk individuals from autism or other neurodevelopmental conditions by compensating for deficits in other brain systems.112

Individuals with autism often have a preference for, and superiority in, processing of local rather than global sensory-perceptual features (table 4). Individuals without autism often show the opposite profile. This difference could explain the excellent attention to detail, enhanced sensory-perceptual processing and discrimination, and idiosyncratic sensory responsivity (ie, hyper-reactivity or hyporeactivity to sensory input or unusual interest in sensory features of the environment) in autism. It could also contribute to the exceptional abilities disproportionately recorded in individuals with autism.113 and 114 Additionally, top-down information processing in individuals with autism is often characterised by reduced recognition of the global context,115 and a strong preference to derive rule-based systems.113 The neural bases are spatially distributed and task dependent, but converge on enhanced recruitment of primary sensory cortices, reduced recruitment of association and frontal cortices involved in top-down control,116 and enhanced synchronisation of parietal-occipital circuits.117

Neurobiology

Neurobiological investigation has identified patterns of brain perfusion and neural biochemical characteristics, which are described elsewhere.118 and 119 Additionally, systems-level connectivity features and plausible neuroanatomical, cellular, and molecular underpinnings of autism have been identified. Evidence from electrophysiology and functional neuroimaging (resting-state and task-based connectivity),120 structural neuroimaging (white-matter volume and microstructural properties),121, 122 and 123 molecular genetics (cell adhesion molecules and synaptic proteins, and excitatory–inhibitory imbalance),124 and information processing have given rise to the idea that autism is characterised by atypical neural connectivity, rather than by a discrete set of atypical brain regions. Ideas about the precise way in which connectivity is atypical vary, from decreased fronto-posterior and enhanced parietal-occipital connectivity,117 and 125 reduced long-range and increased short-range connectivity,126 to temporal binding deficits.[url=http://

最后编辑于 2022-10-09 · 浏览 2.3 万