【共享】《世界银行经济评论》文章:“中国‘失去的女孩’的后果

The Consequences of the “Missing Girls” of China

Avraham Y. Ebenstein and Ethan Jennings Sharygin

作者是Avraham Y. Ebenstein and Ethan Jennings Sharygin(第一作者是伯克利人口系2007年毕业的博士,第二作者是位研究生。前者的研究工作曾批驳过“乙肝流传导致性别比畸形”的说法)。

原文题目:The Consequences of the “Missing Girls” of China

发表于The World Bank Economic Review 2009 23(3):399-425; doi:10.1093/wber/lhp012

这里有原文链接:

http://pluto.huji.ac.il/~ebenstein/Ebenstein_Sharygin_2009.pdf

文章图2是婚龄人口的性别比;图3是不同性别比情况下光棍比例预测:2050年时25岁以上的男性人口很可能有15%无法结婚;图4是可怕的人口结构金字塔;图5是老龄人口比例预测,到2060年65岁以上的人口将达到40%以上、并很可能维持在35%以上(比我上次算的还严重)。

文章还讨论了性别比畸形对**活动、人口迁移、艾滋病传播、传统的养老机制的影响。

文章的结论是,除非政府及时采取措施改革养老体制、调节总和生育率、平衡新生人口性别比,否则光棍带来的问题不可避免。

http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_4b44e2b10100i1b2.html

The Consequences of the “Missing Girls” of China

Avraham Y. Ebenstein and Ethan Jennings Sharygin

In the wake of the one-child policy of 1979, China experienced an unprecedented rise

in the sex ratio at birth (ratio of male to female births). In cohorts born between 1980

and 2000, there were 22 million more men than women. Some 10.4 percent of these

additional men will fail to marry, based on simulations presented here that assess how

different scenarios for the sex ratio at birth affect the probability of failure to marry

in 21st century China. Three consequences of the high sex ratio and large numbers of

unmarried men are discussed: the prevalence of prostitution and sexually transmitted

infections, the economic and physical well-being of men who fail to marry, and

China’s ability to care for its elderly, with a particular focus on elderly males who fail

to marry. Several policy options are suggested that could mitigate the negative consequences

of the demographic squeeze. JEL codes: I18, J11, J12, J13, J26, N35

In an attempt to halt explosive population growth in China, the framers of the

one-child policy of 1979 projected that if every woman of childbearing age had

an average of 1.5 children, China would reach a peak population of approximately

1.2 billion in 2030, slowly declining thereafter to an ideal level of 700

million by the late 21st century (Yu 1980, projection 4). While these projections

were remarkably accurate considering the available information, officials

did not fully anticipate the impact of the fertility controls on the sex ratio at

birth (the ratio of male to female births) and the social consequences of high

sex ratios.1

Avraham Ebenstein is a Robert Wood Johnson Scholar in Health Policy at Harvard University; his

email address is aebenste@rwj.harvard.edu. Ethan Sharygin ne´ Jennings (corresponding author) is a

Ph.D. student at the Population Studies Center at the University of Pennsylvania; his email address is

garba@pop.upenn.edu. The authors thank Steven Leung for excellent research assistance, Sharona

Shuster and Claudia Sitgraves for their careful editing, and Monica Das Gupta and Bill Lavely for their

helpful comments and suggestions. An additional debt of gratitude is owed for the careful attention of

four reviewers—the journal editor and three anonymous referees.

1. Song Jian, a leading scientist and politician credited with innovations in science and mathematics,

was charged with developing policies to put China’s population trajectory on the optimal path

(Scharping 2003). This second-best scenario (after the ideal of one child per couple) was projected to

result in a total population of 1.17 billion in 2025, declining to 777 million by 2080. While Song’s

projections did not incorporate the dramatic change in the sex ratio of births following introduction of

the one-child policy, they did account for the already higher sex ratio of births in China.

THE WORLD BANK ECONOMIC REVIEW, VOL. 23, NO. 3, pp. 399–425 doi:10.1093/wber/lhp012

Advance Access Publication November 5, 2009

# The Author 2009. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the International Bank

for Reconstruction and Development / THE WORLD BANK. All rights reserved. For permissions,

please e-mail: journals.permissions@oxfordjournals.org

399

Government controls on marriage and childbirth instituted in the 1970s

were intended to reduce population growth through delayed marriages, longer

gaps between births, and lower lifetime fertility, a set of policies known as wan

xi shao (later, longer and fewer). In 1979, a countrywide one child per couple

policy was introduced. As the policy was codified and policy enforcement diffused

throughout the country over the 1980s, parents unhappy with the prospect

of never having a son became an increasingly common phenomenon. For

many parents, intense son preference and the introduction of sex-selective abortion—

made possible by the legalization of abortion after 1979 and the introduction

of ultrasound technology in the early 1980s—led to a “merger of

Eastern philosophy and Western technology.” As a consequence, cohorts born

between 1980 and 2000 included 22 million more men than women, a

phenomenon known as the “missing girls” of China. According to projections

in this article, approximately 10.4 percent of the men in these cohorts can be

expected to fail to marry.

The popular press is replete with predictions that the vast number of unmarried

men will destabilize Chinese society and represent a “geopolitical time

bomb.”2 Hudson and den Boer (2004) argue that the high sex ratios in China

will be associated with an increase in crime, since most violent crime is committed

by unmarried young men. They also suggest that the poor marital prospects

for these men may lead to China taking a more aggressive stance in world

affairs, as happened before. In the 18th century, the Qing dynasty government

responded to the rising sex ratios brought about by high levels of female infanticide

by encouraging single men to colonize Taiwan. And in the 19th century,

poor economic conditions in Shandong province led to rampant female

infanticide and a subsequent rebellion when the unbalanced cohorts matured

and organized an uprising against the Qing dynasty (Poston and Glover 2004).

The relevance of such examples to modern China is unclear, since empirical

evidence is lacking on the connection between large numbers of single men and

social upheaval. The potential consequences of this gender imbalance has

spurred research in several disciplines, including demography, political science,

and economics, but more work on the direct causal links between high sex

ratios and social disorder is warranted.3

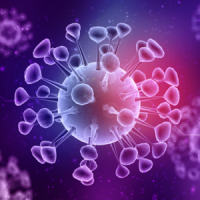

High sex ratios at birth have several predictable consequences, which this

article analyzes. It finds that the growing population of unmarried men will affect

the prevalence of commercial sex activity and the transmission of sexually transmitted

infections, including HIV. And men who fail to marry may be worse off

economically and will not have children to support them in their old age.

2. Michael Fragoso, “China’s surplus of sons: a geopolitical time bomb,” Christian Science

Monitor, October 19, 2007. Retrieved from www.csmonitor.com/2007/1019/p09s02-coop.html)

3. Edlund and others (2007), exploiting time variation in the introduction of China’s one-child

policy to estimate the impact of high sex ratios on crime rates, find that the rising sex ratio explains a

third of China’s recent increase in crime rates.

400 THE WORLD BANK ECONOMIC REVIEW

Understanding the social and economic consequences of high sex ratios in

China is critical in light of the persistence of this phenomenon since the advent

of the one-child policy. The high sex ratios of cohorts born in the past two

decades have already altered the demographic destiny of China. The shortage of

women lowers the reproductive potential of the population and accelerates the

shrinking of the population in the 21st century, absent a return to replacement

fertility rates (Cai and Lavely 2005). Recent Chinese government figures indicate

that the female deficit has actually worsened since the 2000 Census, with the

official sex ratio at birth reaching 120 boys for every 100 girls in 2008 (China

National Population and Family Planning Commission 2009).4 Unless action is

taken to reverse this trend, the negative consequences appear all but inevitable.

This article is organized as follows. The first section presents background

information on marriage and fertility and uses population simulations to assess

how different scenarios for changes in the sex ratio at birth and the total fertility

rate could affect the share of men who fail to marry in China over the next

century. Section II discusses the expected consequences of the high sex ratios

and the failure of men to marry for migration, commercial sex activity, and the

prevalence of sexually transmitted infections, with a focus on HIV. Section III

explores the implications of the sex imbalance on China’s ability to care for its

elderly in an aging population with a growing number of unmarried, childless

men. Section IV briefly discuss the benefits of marriage using indicators of

economic and physical well-being and examines the welfare impact of the

failure to marry on health and financial outcomes. Section V briefly discusses

current efforts by the Chinese government to address the consequences of the

skewed sex ratio and summarizes several policy recommendations for China in

light of the anticipated costs of this worrisome demographic pattern.

I . DEMOGR A P H I C CONSEQUENCE S OF CH INA’ S “MI S S ING GI R L S ”

This section contains background information on marriage and fertility in

China and presents several scenarios on how changes in the sex ratio at birth

and the total fertility rate could affect the share of men who fail to marry in

China over the next century

Marriage, Fertility, and Sex Ratios in China

The failure of men in China to marry because of a shortage of women is not

an entirely new phenomenon. High sex ratios could be observed even in the

19th century, when missionaries reported that women they interviewed indicated

very high rates of female infant mortality (Coale and Banister 1994).

China’s 1982 Census shows that nearly 6 percent of men born between 1935

and 1945 failed to marry, compared with less than 2 percent of the women

4. A discussion of alternative calculations of the sex ratio of new births is available in Goodkind (2008).

Ebenstein and Sharygin 401

(table 1). Marriage prospects for men born between 1945 and 1955 were only

slightly better, with 5.5 percent failing to marry.5 Chinese men who remain

single are known as “bare branches” (guang gun), since they will fail to extend

the family tree. In each cohort since 1935–45, unmarried men have lower literacy

rates than men who marry. The concern over these “bare branches” is

thus partly due to the distributional consequences of this phenomenon, since

men with the worst economic prospects are generally forced to bear the

additional burden of remaining single.

Relative to earlier (and later) cohorts, men born during China’s baby boom

of the 1950s and 1960s had better prospects. Higher fertility rates in these

decades were associated with less distorted sex ratios, since parents were able

to have a son without resorting to sex selection. This population growth

allowed men to select brides from a larger group of younger women. The age

gap between men and women at first marriage decreased as men were able to

marry at a relatively younger age (figure 1).

China is on the cusp of a dramatic deterioration in men’s marital prospects.

The sex imbalance between potential spouses of the same age group is forecast

TABLE 1. Marriage Rates for Men in China, by Decadal Birth Cohorts,

1935–45 to 1955–65 (percent)

Category

1935–45 1945–55 1955–65

Men Women Men Women Men Women

Share never married 5.88 0.18 5.49 0.29 3.82 0.38

Sex ratio of cohorts (ratio of men to women) 1.14 n.a. 1.08 n.a. 1.04 n.a.

Share illiterate, ever-married men 20.8 n.a. 7.7 n.a. 1.1

Share illiterate, never-married men 48.6 n.a. 33.3 n.a. 12.7 n.a.

n.a. is not available.

Note: The share never married and the sex ratio of the cohorts in each column is calculated

using data on individuals observed in these cohorts. The observed sex ratios are slightly higher

than at the time these individuals were of marrying age, since adult mortality rates are higher for

men than for women. Age at marriage is calculated using the 2000 Census, and so the sample is

restricted to men born in these cohorts and still living at the time of the census.

Source: Authors’ analysis based on data from China National Bureau of Statistics (1982,

2000) and China Population and Information Research Center (1990).

5. One surprising finding is that the marriage rate was very high for cohorts of men born between 1935

and 1944 (almost 95 percent), despite the high sex ratio in these cohorts. The ratio of men to women was

roughly 1.14, so more men might have been expected to fail to find a spouse. One explanation for the high

marriage rate among these men is that the sex ratios of cohorts entering the marriage market in the 1960s

were falling. Many of the men from previous cohorts delayed marriage and married women from these

younger cohorts. Intuitively, the observed increase in the age gap in spouses of a full year implies that on

average men delayed marriage one year and thus had an additional cohort of women to choose from (given

that women do not generally marry men their age or younger men). Men’s ability to marry women in

younger cohorts has the potential to mitigate sex ratio distortions in any particular cohort. Such adaptation

was also observed in England following World War I and in other contexts where people feared a collapse

in the marriage market, but none occurred (Bhrolchain 2001).

402 THE WORLD BANK ECONOMIC REVIEW

to be at its worst by 2020, as the cohorts with the highest sex ratios (those

born under the one-child policy) reach adulthood (figure 2). This projection

holds under the conservative assumption that the campaign to achieve a target

sex ratio of 1.09 has been successful in the most recent period for which no

FIGURE 1. Average Age at Marriage by Sex and Spousal Age Gaps, China

1940–2000

Source: Authors’ analysis based on data from China National Bureau of Statistics (2000).

FIGURE 2. Sex Ratio of Marriage-Age Adults in China, 1950–2030

Note: The marriage market is defined as men ages 22–32 and women ages 20–30. The sex

ratio for each year is calculated using data from the 2000 Census, modeling population changes

with age–sex–year specific mortality rates. The population is simulated forward from 2000 using

baseline fertility assumptions (explained in the text) and a sex ratio at birth of 1.09 from 2005

and beyond. The vertical dotted line indicates data from the 2000 Census.

Source: Authors’ analysis based on data from China National Bureau of Statistics (1982,

2000).

Ebenstein and Sharygin 403

birth data are available.6 Fertility has been falling in China for decades, for a

number of reasons. Improvements in health have improved the survival rates of

children to adulthood, greater economic competition has increased the level of

investment necessary for each child, and government policy has encouraged

family planning to various degrees.7 This demographic transition, however, is

made more profound by the policy climate in China, especially legislation regulating

minimum age at marriage and the one-child policy. As birth cohorts age,

they find that each successive generation is smaller than their own, giving rise

to a kite-shaped age distribution in many Asian countries.

There is a discrepancy between the geographic areas with the highest sex

ratios of children in China (map 1) and those with the largest shortage of

women of marriageable age (map 2). The sex ratios of children—reflecting

how strongly parents manifest a son preference—are highest in the Han

majority areas of Eastern China. By contrast, the sex ratios at marriageable

MAP 1. Sex Ratio of Children, Ages Birth to 15

Source: China National Bureau of Statistics (2000)

6. In contrast, the 2008 revision of the UN World Population Prospects projection for China assumes

that this level of sex ratio balance is not attained until 2050 (United Nations Population Division 2009).

7. Contraceptives, banned before 1953, became widely available after the government’s first birth

control campaign in 1957 (Hemminki and others 2005).

404 THE WORLD BANK ECONOMIC REVIEW

ages are highest in the non-Han regions to the west, south and north. These

are also the more remote and poor regions of China, where employment

opportunities have grown far more slowly than in Eastern China. If men

living in regions with better economic prospects are able to draw brides from

poorer areas, it would appear to provide additional evidence for the suggestion

made by many observers that Chinese society tends toward hypergamy

(marriage with a person of a higher social class or position; Parish and Farrer

2000).

Projecting the Number of Unmarried Men in China over the Next Century

Projecting the number of unmarried men in China depends on sex ratios in

future marriage markets, which in turn depend on the sex ratios at birth of

future cohorts and population growth rates. This section describes the derivation

and results of population simulations that capture the anticipated effect

of high sex ratios on the number of unmarried men over the 21st century.

Decline in fertility could exacerbate the impact of the sex ratio imbalance,

since future cohorts of men would be unable to find brides in younger and

MAP 2. Sex Ratio of the Marriage Market, Ages 20–30

Note: The marriage market is defined as men ages 22–32 and women ages 20–30.

Source: China National Bureau of Statistics (2000)

Ebenstein and Sharygin 405

smaller cohorts. But fertility rates in China are still a matter of scholarly debate.8

The simulations presented here assume a total fertility rate of 1.45, based on

China’s National Bureau of Statistics (2005b) estimate from 2004 survey data,

except where otherwise noted.9

The potential trajectories for the sex ratio at birth in China from 2006 to

2100 are summarized in four scenarios. The first scenario assumes an immediate

correction in the sex ratio at birth to 1.06, which is overly optimistic but

represents a lower bound for the analysis. The second scenario assumes that

official policy such as the Care for Girls campaign is effective at stabilizing the

sex ratio at birth at 1.09, a level identified as a government target, although

there is no sign that this target will be achieved soon (Li 2007). The third scenario

assumes that the sex ratio at birth in 2005 of 1.18 persists indefinitely,

and the fourth scenario assumes a further deterioration of the ratio to 1.25.

The simulation model allows for variations in fertility rates and the sex ratio

of new births. The estimates here assume modest increases in fertility to 1.75

births per woman by 2010, although the choice of this date is not theoretically

important. A return to replacement fertility without a concomitant adjustment

in the sex ratio of new births will have only a minor effect in the long run on

the percentage of the population failing to marry since it merely redistributes

additional women to marginally older men (see Supplementary Appendix S1,

at http://wber.oxfordjournals.org/, for additional fertility scenarios).

The simulations use age-specific mortality rates reported by Banister and

Hill (2004) and essentially assume no improvement in life expectancy from

2000 onward. The marriage rule assumes that men marry all available women

three years older or younger than they are until the supply of marriageable

women is exhausted. Though a simplification of real marriage markets, the

process nonetheless demonstrates the essential properties of a marriage market

in which marriageable women become increasingly scarce because of both

below-replacement fertility and an imbalanced sex ratio. The most realistic

scenario that mitigates the serious consequences of the unmarried men

8. Data from the 2000 Census indicate a total fertility rate of 1.22 children in the prior year (China

National Bureau of Statistics 2000). However, some argue that census officials were given misleading

information out of a fear of punishment by parents who had violated the one-child policy (Retherford

and others 2005). Such undercounting affects both fertility estimates and the observed sex ratio.

However, Cai and Lavely (2005) found that 71 percent of the missing girls in the 1990 census were still

missing in 2000. Also, the sex ratio of children ages birth to 4 in 2000 conforms well to the male to

female ratio of children ages 5–9 in 2005 (1.19) from the China National Bureau of Statistics (2005a)

One Percent Inter-Census Population Survey of China. While not decisive, these findings suggest that the

undercounting issue is surmountable. Additional values for these parameters were included in the

analysis here because of the remaining uncertainty about the extent of the undercount phenomenon. Cai

(2008) summarizes the debate on China’s total fertility rate and estimates a value of 1.5–1.6, in line

with other third-party estimates.

9. These projections forecast a continuation of current trends, including modest increases in fertility

at all ages. Many forecasts predict a rapid return to replacement fertility rates (Peng 2004). A

supplemental appendix to this article, available at http://wber.oxfordjournals.org/, explores the

sensitivity of the results to different fertility scenarios (table S1.2). The crucial assumption is not how

population changes, but how the relative supply of men and women will change as fertility changes,

which will be affected by the population size but will be less important than the sex ratio at birth.

406 THE WORLD BANK ECONOMIC REVIEW

phenomenon is one that addresses both the sex ratio and fertility. To the extent

that marriage norms may change, the simulations overestimate the percentage

of men who fail to marry. However, assortative mating constraints are not

imposed, so the failure to marry rate is underestimated. In the end, these competing

influences should largely cancel each other out. The details of the

matching algorithm and alternative specifications testing the sensitivity of these

results are described in Supplementary Appendix S1.

The results of the simulation are presented in figure 3. Under baseline assumptions,

the share of men ages 25 and older who fail to marry will exceed 5

percent by 2020. As the cohorts born in recent years enter the marriage market

and some share inevitably fail to marry, the population of unmarried men will

rise well beyond this level. In the most optimistic scenario, where the sex ratio

returns to normal immediately in 2006, the share of men who fail to marry will

stabilize at just below 10 percent in 2060. In the second scenario, unmarried

men will represent roughly 10–12 percent of men ages 25 and older. In the

third and fourth scenarios, where the sex ratio at birth persists at either 1.18 or

1.25, the share of men who fail to marry will peak above 15 or 20 percent.

To some extent, these outcomes can be mitigated by realistic increases in both

the age at marriage and the age gap between spouses.10 This idea of demographic

translation was introduced to describe the shift of the age-specific fertility distribution

observed in the postwar baby boom era, but it also applies to the case of sex

imbalance in marriage markets (Foster and Khan 2000; Ryder 1964). This view

FIGURE 3. Share of Men Ages 25 and Older Who Fail to Marry, under Four

Scenarios, 2000–2100

Note: The technical assumptions underlying marriage formation for the simulations are

outlined in detail in Supplementary Appendix S1 available at http://wber.oxfordjournals.org/. The

shares of unmarried men are evaluated for four possible trajectories for the sex ratio at birth,

ranging from an immediate correction to 1.06 to a further deterioration to 1.25.

Source: Authors’ analysis based on data from China National Bureau of Statistics (2000).

10. Edlund (1999) demonstrates that son preference can account for increases in spousal age gaps

and also the pattern of hypergamy.

Ebenstein and Sharygin 407

holds that an excess of men over women in the marriage market can be fully compensated

for by modest increases in men’s age at marriage. Using an estimate of 15

percent excess men over women, it appears that the share of men who fail to ever

marry can be kept close to the historical rate of 5 percent if the gap in age between

spouses reaches eight years by 2050 (see also Supplementary Appendix S1).

This back of the envelope calculation neglects to consider that, because fertility

rates are artificially held below natural replacement rates, each cohort of women

entering the marriage market is smaller than the last. Indeed, the simulation

results are highly sensitive to the assumption about the trajectory of fertility rates.

With a return to a replacement fertility rate in the next decade, the impending

problem of shortages of marriageable women can be averted, albeit by dramatic

increases in both the age at marriage and the age gap between spouses.

However, there are few indications that the total fertility rate will rise to the

natural replacement rate in the near future. The National Population and Family

Planning Commission recently reaffirmed its intention to maintain the policy

status quo for “at least another decade.”11 Moreover, the high sex ratios and

smaller size of birth cohorts under the one-child policy imply that the age gap at

marriage must increase until larger birth cohorts enter the marriage markets

(some 25 years into the future, at the earliest), at which point any social upheaval

associated with shortages of women and delay in marriage will already have

occurred. In the more pessimistic scenarios, where the fertility rate remains

around 1.45 and the sex ratio at birth remains above the natural rate, the age

gap between spouses and age at marriage for men will necessarily rise ad infinitum

as each cohort of men passes along the bride shortage to the next.

I I . “BARE BRANCHE S , ” HIV, PROS TITUTION, AND MI G RAT ION

In light of the large number of men who will delay marriage and who are

anticipated to fail to marry, this section examines some of the potential negative

impacts of high sex ratios.

In China during the early 1990s, growth in the number of people with HIV

was concentrated among intravenous drug users and recipients of tainted blood

transfusions. During the mid-1990s, however, HIV and AIDS began to spread to

new regions and populations not previously considered at risk. As the population

of single men rises, the transmission of HIV through risky heterosexual contact,

particularly commercial sex activity, will become an increasingly severe problem.

Currently, the number of people who are HIV positive who contracted the

disease through sexual contact is as large as the number who were infected

through intravenous drug use. Individuals who contracted the virus from sexual

activity represented half of all new infections in 2005 (China CDC and others

2006). The population that is HIV positive can be broken down into four

groups. Intravenous drug users (90 percent of them concentrated in far western

11. Jim Yardley, “China sticking with one-child policy,” New York Times, March 11, 2008.

Retrieved from www.nytimes.com/2008/03/11/world/asia/11china.html?_r=1.

408 THE WORLD BANK ECONOMIC REVIEW

and southern provinces) account for 44.3 percent of infected people, and those

infected through sex account for 43.6 percent (China CDC and others 2006).12

The third group, those who donated or received blood from commercial blood

donors, account for 10.7 percent, and the remaining 1.4 percent of infected

people are those who were infected through mother-to-child transmission.

Considering the impending demographic pressures as heavily male birth

cohorts enter adulthood and encounter shortages of marriageable women, female

sex workers are an important at-risk group that has been understudied as an HIV

vector. In the 1980s, sex workers represented a small share of the population, but

between 1990 and 2000, prostitution expanded rapidly. Current estimates range

from 1 million women whose primary income comes from commercial sex to up

to as many as 10 million women engaging in paid sex of some kind.13

Recent evidence indicates that Chinese men are more likely than U.S. men to

have paid for sex and that young Chinese men are more likely than older men

to have visited a prostitute: 12.6 percent of men ages 21–30 and 8.8 percent of

men ages 31–40 have been to a prostitute.14 Moreover, Chinese men are less

likely than their U.S. counterparts to report that they use condoms regularly,

which places them at higher risk of sexually transmitted infection. While HIV

rates among prostitutes are difficult to measure, the HIV prevalence rate

among sex workers in Guangdong, Guangxi, and Yunnan provinces was as

high as 11 percent in 2000,15 and it seems reasonable to assume that the risky

sexual practices of illegal sex workers place them at higher risk of exposure.16

While not all single men will patronize sex workers, and married men will

also pay for sex, documenting the relationship between demographic change

and commercial sex activity is important, as the population of single men will

grow in the years to come.17 Identifying specific groups of men who are more

prone to patronize sex workers is also important because of the need to target

public health interventions to the groups most at risk.

To analyze the relationship between numbers of men in at-risk groups and

commercial sex activity, data from the Chinese Health and Family Life Survey

were used to calculate the percentage of men reporting having paid for sex, for

12. The provinces with the highest levels of intravenous drug use (90 percent of it heroin) are Yunnan,

Xinjiang, Guangxi, Guangdong, Guizhou, Sichuan, and Hunan. The share infected through sex includes

those who contracted HIV from sex with a sex worker (19.6 percent of the total number of people infected

with HIV), from an infected partner (16.7 percent), and from sex with men (7.3 percent).

13. Maureen Fan, “Oldest profession flourishes in China,” Washington Post Foreign Service, August 5,

2007. Retrieved from www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/08/04/AR2007080401309.

html.

14. Authors’ calculation from the Chinese Health and Family Life Survey data (Population Research

Center 2000). For comparable estimates, see Parish and Pan (2006).

15. This calculation is based on sex workers in detention centers, since prostitution is illegal in

China (Settle 2003).

16. SeeMerli and others (2006) for an epidemiological model of sexual transmission of HIV in China.

17. To date, research has not been conducted on the relationship between the size of the single-male

population and the supply of sex workers. While most researchers assume that the population of sex

workers will increase as demand for their services increases, it could also be the case that the marriage

squeeze for men may improve the marriage prospects of female sex workers and thereby take them off

the sex market. This is a promising area for future research.

Ebenstein and Sharygin 409

six regions (Population Research Center 2000). Paying for sex was most

common in the coastal southern region, encompassing the provinces of Fujian

and Guangdong, followed by the coastal eastern region including Jiangsu,

Shanghai, and Zhejiang Provinces and the far northeastern provinces bordering

the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and the Russian Federation. The

majority of counties where a high percentage of men report having paid for sex

tend to be counties with high percentages of single men. (Data on commercial

sex activity are unavailable for Inner Mongolia, Tibet, and Xinjiang provinces.)

Among single men, young migrant construction workers make up a distinct

at-risk population who are particularly likely to pay for services from low-cost

female sex workers and are less likely to be educated about sexually transmitted

infections and condom use (Garfinkel and others 2005). A pronounced relationship

is found between the density of construction activity and the prevalence of

commercial sex activity. In the urban provinces of Guangdong, Fujian, Jiangsu,

Shanghai, and Zhejiang, more than 7 percent of men report having ever paid for

sex. These and other areas of dense concentration of the construction industry,

such as northern Shandong Province and the counties surrounding Beijing,

merit particular attention from public health policy.18

The potential for an increase in HIV infection rates fueled by migrant

workers has attracted the attention of many researchers. Tucker and others

(2005) present compelling evidence that rising rates of sexually transmitted

infection in cities are due to the sexual practices of migrant workers, who are

demographically similar to the men who are projected to fail to marry: poor,

uneducated, and single. Chen and others (2007, p. 1658) analyze HIV rates

among a sample of patients being treated at 14 Guangxi clinics for sexually

transmitted infections and conclude that “China’s imbalanced sex ratios have

created a population of young, poor, unmarried men of low education who

appear to have increased risk of HIV infections.” A multivariate analysis of

factors that affect HIV status yields an odds ratio of 1.7 for single people relative

to those who are married and 1.4 for men relative to women.

To determine how migration might affect the transmission of HIV, especially

migration to China’s growing urban centers, it is helpful to examine current and

expected migration patterns. Comparing the geographic distribution of sex ratios

at birth with the distribution of sex ratios among the current adult population

reveals the regions from which migration is likely to occur in the future (see maps

1 and 2). Particular attention should be paid to counties where the sex ratio is

abnormally high and where HIV prevalence is also high, such as the southwestern

provinces of Guangdong, Guangxi, and Yunnan (Lu and others 2006). As the

cohorts of men younger than 15 enter adulthood and experience demand–supply

imbalances in marriage markets, the likelihood of commercial sex encounters and

other risk-taking behavior increases. This dynamic is likely to be strongest in areas

where the risk of contracting HIV is highest. At the same time, as women migrate

18. The results for men in the construction industry are included in Supplementary Appendix S2.

410 THE WORLD BANK ECONOMIC REVIEW

to wealthier coastal cities to maximize their marriage prospects, these young men

will also face pressure to migrate to cities, and both groups could bring HIV from

the countryside to cities. Results by Yang (2006) confirm fears that male migrants

experience elevated rates of HIV infection.19

The connections between cohort-specific sex ratios, prostitution rates, and

HIV transmission are complex, but it is clear that these factors are all responsible

for the rising HIV rates in China. Given the correlation between percentages

of unmarried men and commercial sex activity, how will the increase in

sex ratios and the ensuing failure of many men to find marriage partners affect

markets for sex? The results of a simple simulation show how the incidence of

prostitution might evolve (table 2). The simulation projects the share of men

who pay for sex, assuming that the gender, marital status, and age-specific

rates of having paid for sex found in 2000 persist during the 21st century. The

Chinese Health and Family Life Survey finds that 14.7 percent of single men

and 7.3 percent of married men admit to having paid for sex in 2000

TABLE 2. Share of Men Ages 25 and Older Paying for Sex, and Simulated

HIV Prevalence in the Entire Population, by Sex Ratio at Birth, 2000–30,

2050, and 2070 (percent)

Category

Sex ratio at birth

1.06 1.09 1.18

2000 2010 2020 2030 2050 2070 2050 2070 2050 2070

Paid for sex 6.28 6.92 7.78 8.35 8.36 8.26 8.42 8.40 8.59 8.76

HIV prevalence 0.031 0.046 0.065 0.076 0.093 0.095 0.094 0.097 0.097 0.103

Note: The simulations profile behavior based on the age, sex, and marital status of the population.

Rates of having paid for sex in these groups are imputed using calculations from the

1999/2000 Chinese Health and Family Life Survey (Population Research Center 2000). The HIV

simulations assume an odds ratio of 1.4 of men to women and a 1.7 odds ratio of single to

married individuals (Chen and others 2007). The total count of HIV positive population in

2000–10 by this method is between the low and medium estimates of the Joint United Nations

Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS, various years). Results before 2030 do not differ appreciably

by sex ratio at birth because of known characteristics of the population in 2000.

Source: Authors’ analysis using data from China National Bureau of Statistics (2000).

19. A study by Parish and Pan (2006) found no significant difference in the risk of HIV contraction

between urban men and low-status male migrants. If confirmed, this could mean a reduced likelihood that

male migrants will carry HIV to cities, although female migrants may still play the same role. Many

migrants may eventually marry, which could decrease the spread of HIV (by reduced prevalence of

commercial sex or by containing the geographic spread of HIV if migrants return home to marry). Many

men will lack the means to migrate to urban regions or will leave the city after a time with new wealth and

marry at home. An anonymous reviewer noted that poor rural men have been less likely to migrate and that

those that do migrate are still more likely to partner with women in their home region. Going forward, it

can be expected that rural men who migrate to cities will be forced to compete with urban men for sex and

mates and therefore will be more likely to visit prostitutes, presenting a problem even if these men eventually

return home with wealth and marriage prospects. The conflicting results leave room for further study.

Ebenstein and Sharygin 411

(Population Research Center 2000).20 That information, plus the age profile of

commercial sex activity, can be used to calculate a hazard rate of the chance of

visiting a prostitute over the life cycle.

Although this calculation is admittedly imprecise, in that current rates of

having paid for sex represent a lower bound on the future prevalence of prostitution

(due to increased levels of future migration from rural to urban areas),

the results show an increased demand for commercial sex among Chinese men.

Assuming continuation of current behavior patterns, increases in the sex ratio

at birth will create a modest increase in the share of men paying for sex.

Changes in policy, income, or sexual culture will likely be more important in

the future. Nevertheless, the simulations indicate that, almost immediately,

demographic change alone will contribute to 2–3 percentage point increase in

the share of men paying for sex in the next 30 years.

The simulations of how demographic change will affect China’s HIV infection

rate in the 21st century assume that the unknown hazard rate for HIV

infection by age and sex generates 650,000 cases (the current estimated

number of HIV cases in China) when applied to the population ages 22–40 in

2006. The share of the population that is HIV positive is then imputed to each

cohort by sex, age, and marital status using the odds ratios from Chen and

others (2007). Thus, these simulations attempt to model how HIV infection

rates will change driven solely by changes in the demographic structure of

China as cohorts with higher percentages of single men enter their sexually

active years. The results indicate that the infected population will increase precipitously

over the next 30 years and stabilize at a higher rate of infection. As

with the results for patronage of commercial sex, the effect of variation in the

sex ratio at birth on HIV transmission is limited. Variation in the sex ratio at

birth between 1.06 and 1.25 (not shown) results in HIV infection rates in 2050

of 0.93–1.05 per 1,000. The greatest increase in HIV incidence, from 0.3 infections

per 1,000 in 2000 to 0.76 per 1,000 in 2030, is a result of momentum

from the known characteristics of the population in 2000.

While these projections do not incorporate increases in the probability of

contracting the disease that might result as more people become infected, they

also do not assume any improvement in preventive behavior. Since the Chinese

government is beginning to respond to the impending HIV crisis, there is

reason to hope that these projections are overly pessimistic. The central government

and local authorities show signs of recognizing the growing role of sex

workers in HIV transmission, and several pilot projects promoting safer sex

(practices such as condom use) are in place in Beijing, Fujian, Hubei, Jiangsu,

and Yunnan. Government budget allocation for HIV/AIDS efforts grew from

approximately $12.5 million in 2002 to about $100 million in 2005 and $185

20. These percentages are derived from a regression of an indicator for having paid for sex on

several demographic control variables, including marital status. See also the discussion of similar results

for these data in Parish and Pan (2006).

412 THE WORLD BANK ECONOMIC REVIEW

million in 2006.21 The government is also treating more cases of HIV, with

projects such as the China Comprehensive AIDS Response (CARES) campaign,

a program initiated in 2003 to supply domestically manufactured antiretroviral

AIDS medication free to anyone who contracted the disease through tainted

blood transfusions. The effectiveness of such efforts will be critical in containing

the virus as the sex ratio rises and the percentage of those who are married

falls among the sexually active population.

I I I . SU PPORT OF THE CH I L D L E S S ELDERLY

This section examines the impact of China’s changing demographic structure,

with a growing population of unmarried and potentially childless men, on its

ability to care for its elderly. China’s age distribution in 2000 exhibits two pronounced

spikes, both emerging as a legacy of its demographic transition

(figure 4). In the 1960s, the total fertility rate exceeded 6, and this baby boom

resulted in a large cohort of people ages 30–40 in 2000.22 The second baby

boom occurred when these cohorts began to have children, and so the number

of children born in the 1990s was also large. However, in the wake of

government-mandated fertility control, each successive cohort in China has

been smaller than the previous one.

Although China’s population is more than four times that of the United

States, it has less than three times as many births.23 In 2030, the children born

in the second baby boom of the 1990s will still be in their most productive

working years and presumably will provide support (fiscal or otherwise) for

the elderly. However, by 2050, the population forecast for China is far worse

than that for the United States (see figure 4).24 The elderly dependency ratios

will be alarmingly high in China, with large numbers of people entering old

age without young workers to replace them. In contrast, even without further

immigration, the United States can anticipate a more favorable age distribution

by 2050, with a relatively young workforce and very few baby boomers left in

the population of elderly.

While retirement funding for social security programs in urban areas is

receiving research and analysis, the looming problems among the population of

rural peasants—who make up roughly 70 percent of China’s 1.3 billion

21. “Spending on HIV/AIDS prevention set to double,” China Daily, December 28, 2005. Retrieved

from www.chinadaily.com.cn/english/doc/2005-12/28/content_507212.htm.

22. Some researchers identify this bulge in the population as one explanation for China’s recent

rapid economic growth. This phenomenon, when a large cohort of workers, preceded and followed by

smaller cohorts reaches its most productive period in the labor force, is known as the “demographic

dividend.”

23. In China, only 10.6 million children were born in 1999 (and survived to 2000) compared with

3.8 million in the United States.

24. As projected in Alternative Scenario I of the 2007 Trustees Report by the U.S. Social Security

Administration (U.S. SSA 2007).

Ebenstein and Sharygin 413

people—are potentially much larger, even though there are no explicit financial

promises to this population, such as social security or government-provided

medical care. As Lee (1994) discusses, the allocation of resources for old age

support can be mediated by financial markets, public sector programs, or intrahousehold

transfers. In the absence of financial wealth or social insurance,

most of the elderly in rural China rely on intrahousehold transfers. A recent

FIGURE 4. Age Structure in China and the United States in 2000 and 2050

Source: For China, authors’ simulations based on data from China National Bureau of

Statistics (2000); for the United States, authors’ analysis based on data from 2000 Census and

projections by the U.S. Social Security Administration (U.S. SSA 2007).

414 THE WORLD BANK ECONOMIC REVIEW

survey of heads of rural households found that 62 percent anticipate that their

children will be the primary source of elder care, while only 29 percent list personal

savings as the anticipated source of support.25 Inadequate preparation

for old age among the rural peasant population may lead to severe financial

hardship and consequently to political instability. Already, China’s growing

income divide between urban and rural residents is arousing concern.

Differences in access to financial resources and social insurance may well contribute

to this problem as the population ages and the need to provide for the

elderly becomes more pressing.

Combined with the findings in the following section on asset accumulation

by marital status, the failure to marry could have severe consequences for the

distribution of wealth among elderly men. Men who are able to marry and

have children will be distinctly advantaged over those who must delay their

marriages until old age or who remain unmarried. The financial markets and

public sector programs necessary to guarantee equity by replacing the intrahousehold

transfer system are not in place. Thus an important area for future

development is the creation of public or private investment mechanisms for

men facing extended singlehood to provide for their health and financial wellbeing

in advanced age.

The share of elderly in China will rise dramatically during the 21st century

(figure 5). By 2060, when the very large cohorts come of age, China’s over-65

FIGURE 5. Share of China’s Population Ages 65 and Older, 2000–2100

Source: Authors’ simulations as described in the text.

25. Authors’ calculation from the 2002 Survey of Rural Households in China (China National

Bureau of Statistics 2002). A smaller share of people ages 20–30 list children as their primary source of

old age support, but the share is still over half (51.3 percent).

Ebenstein and Sharygin 415

population will exceed 35 percent of the overall population.26 This aging of the

population occurs against the backdrop of an emerging generation of unmarried,

childless men.27 China’s traditional cultural assumption is that the elderly are

cared for by their children, and living patterns and fertility decisions are predicated

on the presumption of familial support. The state has made some effort to

promote retirement homes (yang lao yuan), especially in rural areas, but these

efforts have met limited social acceptance or private investment interest.28

China’s population aging over the next 50 years has already been determined

by the current age structure. It will coincide with the emergence of a

new group of permanently unmarried men that will impose a large and increasing

cost on Chinese society, especially in 2050 and beyond. This problem,

common to all countries with a below-replacement fertility rate, is especially

acute where selective abortions have altered the sex ratio. A preference for sons

in China is at least partly economic, since sons have traditionally been the most

important source of old age support. Increased acceptance of daughters could

reduce welfare in old age if the additional girls are a couple’s only child and if

virilocality remains a social norm. In China, however, unlike in Italy or Japan,

for example, the possibility of fertility returning to the replacement level seems

much brighter because in China fertility may be significantly more responsive

to public policy changes.29 Actions taken today to allow Chinese to have larger

families could improve the support ratio and might also allow more couples to

have a son without resorting to sex selection, thus helping to reduce the

number of unmarried men in these cohorts.

IV. MA R I TAL S TATUS AND WE L FARE

This section examines the relationship between welfare and marital status, documenting

the greater poverty, poorer health, and shorter life expectancy among

men who fail to marry, and possible developments in household bargaining

between spouses.

The Census and the China Household Income Survey indicate that failure to

marry is associated with lower income, less financial wealth, and poorer health

(table 3 and Supplementary Appendix S2, table S2.1). The selection of healthier,

higher earning men into marriage is partly responsible,30 although there

26. The 2008 revision of World Population Prospects projects that 23.3 percent of the population

will be 64 or older in 2050 (United Nations Population Division 2009). The comparable figures for the

United States are 20.8 percent in 2050 and 21.6 percent in 2060 (U.S. SSA 2007, Scenario II).

27. Divorce or out of wedlock births are uncommon in China, so for most of these men, a failure to

marry because of a shortage of women will imply a failure to have children.

28. “China vows to promote home care for elderly” Xinhua News Agency, February 22, 2008.

29. Supplementary Appendix S1 presents results of the model for several scenarios that assume a

more rapid or slower pace of fertility growth, reaching replacement level at different dates.

30. Lillard and Panis (1996) present evidence that, in the United States, less healthy men marry

earlier and remarry more quickly following divorce, suggesting that negative selection into marriage by

health is also a potential confounding factor.

416 THE WORLD BANK ECONOMIC REVIEW

is some evidence in other countries that men’s wages rise after marriage,

suggesting a causal link (Korenman and Neumark 1991).

Even after controlling for a respondent’s age, education, ethnicity, and prefecture

of residence, men in China who fail to marry have a third less income,

live in households with an eighth less wealth, and are 11 percentage points less

likely to describe themselves as being in good health than are men who marry.

While the causal link between marriage and welfare outcomes has not been

established in China in the period of interest,31 marriage could theoretically

improve health among married men through reductions in risky behavior and

economies of scale in household welfare (Dre`ze 1997; Lanjouw and Ravallion

1995; Lillard and Panis 1996). A link between marriage and welfare is

especially likely in China, because social insurance programs are limited and

familial support is correspondingly critical to welfare.

The poor financial and health status of unmarried men observed in the

survey particularly manifest in perhaps the most important measure of

welfare—life expectancy. Implied mortality rates of men who married and

those who did not between 1990 and 2000 were calculated by comparing the

number of men in the 1990 and 2000 census data by marital status and calculating

the survival of the artificial cohort (table 3).32 Never-married and evermarried

men who were ages 55–59 in 1990 had similar mortality patterns, but

at older ages the never-married men had higher mortality rates. For example,

among men ages 65–69, the mortality rate was 10 percentage points higher for

never-married men, and less than half of the never-married men survived to the

2000 Census.

The welfare cost of poor health and high mortality for this population of

unmarried men suggests that the high sex ratio at birth could indirectly reduce

TABLE 3. Marital Status and 10-Year Mortality Rates of Men, by Age

Groups

Age

group

Ever-married men

(percent)

Never-married men

(percent)

Difference (percentage

point)

55–59 14.3 15.2 –0.9

60–64 25.7 39.1 213.4

65–69 41.3 51.3 210.0

70–74 59.6 67.5 27.9

75–9 77.1 86.1 29.0

Source: Authors’ analysis based on data from China Population and Information Research

Center (1990) and China National Bureau of Statistics (2000).

31. For other countries, Hu and Goldman (1990) find significant mortality differentials by marital

status (China is not included in their analysis).

32. This calculation assumes that men do not marry for the first time past the age of 55. First

marriage beyond 50 is not observed among any of the respondents in the 0.1 percent sample of the

2000 Census (China National Bureau of Statistics 2000).

Ebenstein and Sharygin 417

the quality and shorten the duration of the lives of never-married men. While

the Chinese preference for sons results in high mortality rates for girls during

pregnancy and infancy, if the relation between marriage and health proves to

be causal, the outcome could be elevated mortality in later years for men

unable to marry because of the shortage of women resulting from the earlier

high mortality rate for unborn and infant girls.

It could also be the case that the shortage of female partners could lead to

increased competition for brides, which could result in behaviors, including

investment in education, that improve the health and well-being of men.33 As

the marriage market tightens, competition for scare women may increase the

bargaining power of married women as well as single women. Evidence from

outside China has shown that greater bargaining power of women, which can

result from gender mismatch in the marriage market, can positively affect

family health and welfare outcomes. These benefits, of course, would accrue to

men who find marriage partners but not to those who remain single throughout

their adult years.34

The evidence presented here suggests that China’s demographic change in

the 21st century will be dramatic and that difficulties in supporting China’s

large elderly population will be compounded by high sex ratios, which will

deny childless men intergenerational support.

V. PO L I C Y RE PONSES TO THE SHORTAGE OF FEMALES I N CH INA

This section briefly summarizes the Chinese government’s policy response to

the problems associated with the high sex ratio and discusses its consequences

and possible alternatives.

When the one-child policy was introduced in 1979, China was only 20

years removed from the Great Leap Forward and the associated famine.

Today, China is rapidly industrializing and experiencing the growth of a

country that can easily feed its estimated 1.3 billion people. If current

trends continue, the population is set to begin declining within the next 20

years. While overpopulation is no longer a pressing concern in China, the

potential consequences of the legacy of missing girls is of immediate

importance.

The alarming increases in sex ratios at birth revealed in the 2000 census

spurred the Chinese government to action, and several programs were

33. An alternative strategy to reduce this uncertainty by identifying the causal direction for marriage

and health and wealth involves finding a factor that affects marriage probability but otherwise has no

influence on welfare. An instrument for marriage is difficult to find in China, since the factors affecting

marital success are so closely related to factors that affect welfare. Panel data would also be useful in

disentangling causality. The regression model presented in table S2.1 in Supplementary Appendix S2

includes controls that are important determinants of marital outcome and explain a good deal of

variation in marital probability in reconstructed cohorts from cross-sectional data.

34. For details, see Lundberg and Pollack (1996) and Rao and Greene (1996).

418 THE WORLD BANK ECONOMIC REVIEW

implemented to address the female deficit. The government’s response can be

classified into two primary strategies: increasing the value of girls in the minds

of parents and reducing the availability of sex-selection technology. The Care

for Girls campaign identified 24 counties with extremely high sex ratios and

provided incentives to reduce the female deficit, including free public education

for girls. Preliminary indications are that these programs are having an effect.

In a joint venture of the Ford Foundation and the United Nations Children’s

Fund (UNICEF), the Chaohu Experimental Zone Improving Girl-Child

Survival Environment, established in 2000, succeeded in lowering the sex ratio

at birth from 125 in 1999 to 114 in 2002 (Li 2007). The government is currently

expanding the Care for Girls campaign to a national initiative. In 2004,

President Hu Jintao declared that the campaign was a top priority and that the

government would work strongly to stop any further rise in the country’s sex

ratio at birth over the next three to five years (Li 2007). Zhang Weiqing, director

of China’s population ministry, estimated that it would take 10–15 years

to return China’s sex ratio to natural level.35

In a second strategy, China is cracking down on sex-selective abortion.

Several legislative initiatives aim to curb the practice and to punish offenders.

The first statutory prohibition on sex-selective abortion came in 1989, and the

most recent family planning law of 2002 bans the use of ultrasound or other

technologies to determine fetal sex. If parents are caught aborting a child on

the basis of sex, health professionals performing the operation are penalized

and parents forfeit any right to have another child (Hemminki and others

2005). In 2006, the government shuttered several fertility clinics for violating

the policy.36 Despite these efforts, however, the sex ratio at birth was 1.18 in

2005, near the all-time high. Enforcement has been weak and uneven, possibly

due to the overriding obligation of local governments to meet stricter population

growth targets. The perceived need for a national policy campaign hints

at an acknowledgment that sex-selective abortions have occurred, and the

timing of higher parity births is further evidence that the practice has continued

(Ebenstein forthcoming).

Efforts to improve funding for old-age security programs have been limited

in scope and have focused on urban areas (Wang 2006). Very limited efforts

have also been made to provide insurance in rural China, but they are insufficient

for dealing with the looming old age crisis. In light of this concern, policy

efforts should be made in two directions. First, China must acknowledge the

implicit obligation to the large elderly rural population forecast for the next

generation, since this generation’s fertility has been too low to enable reliance

on the traditional intrahousehold mechanisms of elderly support. Expanding

35. Interview transcript “Xinwenban jiu jiaqiang jisheng gongzuo he renkou fazhan zhanlv deng

dawen,” Zhongguo zhengfu wang of January 23, 2007. Retrieved from www.gov.cn/zhibo49/wzsl.htm.

36. Joseph Kahn, “China: crackdown on abortion of girls,” New York Times, June 1, 2006.

Retrieved from www.nytimes.com/2006/06/01/world/asia/01briefs-brief-003.ready.html?_r=5.

Ebenstein and Sharygin 419

efforts to provide old age support and to collect the revenue to fund these

initiatives is a top priority. Second, the Chinese government might want to consider

revising its fertility policy. The simulations presented here suggest that the

situation will deteriorate precipitously under the current policy, and higher fertility

in the next decade would help smooth China’s age distribution. Allowing

extra births today will slow China’s demographic decline and establish a larger

supply of workers who could be taxed to fund the baby boom generation

when they reach retirement.

The Chinese government’s recent actions to provide contraception and care

for those infected with HIV are promising developments, but actions to

contain the spread of the disease must focus on the large and growing number

of unmarried men who are at risk. China’s legacy of missing girls will have a

dramatic effect on Chinese society in the 21st century, with increased internal

migration and rising demand for commercial sex all but unavoidable.

Government action is unlikely to effectively reduce the prevalence of commercial

sex, and so policy should aim to reduce the danger of this activity by

raising awareness of the risk of contracting HIV and increasing the availability

of condoms, especially in regions that attract unmarried men. Although

China’s HIV rates are still low, failure to act soon could prove costly, and HIV

might be difficult to contain once it spreads to these unmarried men.

The future course of Chinese policy is yet to be determined. Central government

planners, acknowledging the need to address the son preference, have

chosen to do so through education campaigns, punishment for sex-selective

abortions, and economic incentives for raising daughters. Although the onechild

policy is subject to periodic review, its current fertility targets were

recently reaffirmed despite the desirability of higher fertility for several

reasons.37

The results presented here on some of the potential negative welfare consequences

to having large numbers of men who fail to marry suggest at least two

strategies: increasing fertility, thereby reducing the demand for sex-selective

abortions and slowing population aging, and increasing legal and social incentives

for raising daughters.38 The discussion on revising the one-child policy

has begun (Wang 2005). Many scholars have identified clear links between the

one-child policy and the high sex ratio at birth over the last 20 years, and so an

associated benefit of allowing higher fertility could be a mitigation of the costs

presented here. The simulations presented here also suggest that an impending

imbalance between working age and elderly cohorts in China could be offset

somewhat by higher fertility rates. The simulations also indicate the need to act

quickly. Even if action is taken immediately, China will still have to manage

37. Alexa Olesen, 2007, “China sticking to one-child policy,” Associated Press, January 23, 2007.

Retrieved from www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/01/23/AR2007012300398.html.

38. And reducing incentives for bearing sons, as might be expected to occur with increased

institutional support for elderly and retired workers.

420 THE WORLD BANK ECONOMIC REVIEW

the highly skewed sex ratios in cohorts born over the last 20 years. Addressing

this problem for the second half of the 21st century requires action today.

VI. CONCLUSION

The most significant unexpected consequence of China’s one-child policy is the

decline in the number of female children born to parents who are subject to

strict fertility limits. In time, these missing girls will result in increasing tightness

of the marriage market, with mixed consequences. This article attempts to

establish the magnitude of the expected imbalance as boys born during the

years of abnormally high sex ratios at birth and below-replacement fertility

rates enter the marriage market and find a dearth of female partners. Three of

the most important consequences of this phenomenon are the impact on prostitution,

internal migration, and HIV transmission; the undermining of traditional

old-age support mechanisms; and the impact on the health and

well-being of men in the event of an increase in the failure to marry or, in

demographic terms, in the lifetime celibacy rate.

As sons born during the years of skewed sex ratios reach adulthood and are

unable to find marriage partners, the dangers associated with increased commercial

sex may translate into higher HIV incidence. Simulations, using what is

known about sexual preferences and practices, extrapolated increases in

patronage of sex workers and the incidence of HIV. The imbalance in sex

ratios of adults of marrying age will result in increased opportunities for

women who migrate from rural areas to marriage markets in wealthier areas

but will also put pressure on the men who are left behind to migrate to

cities or to engage in risk-taking behaviors, such as drug use and commercial

sex. The result could be the transmission of HIV from areas of high prevalence

in southwestern and central China to urban centers that have been insulated

so far. The share of men ages 25 and older who have paid for sex is

projected to rise from

最后编辑于 2010-04-06 · 浏览 1167